[This is a continuation of Air Supremacy and Airpower Asymmetry]

F-35s at Hill AFB in Utah

(USAF Photo, Paul Holcomb)

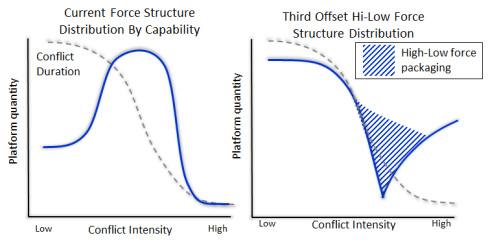

Today’s Air Force fleet structure is in the midst of an identity crisis, full of contradictions and built upon a multi-role fighter foundation. Despite this, the Air Force Future Operating Concept document categorizes its current force structure as a high-low mixture. It defines this mix as, “the intent to acquire a limited number of high-cost/high-capability platforms supplemented with many lower-cost/lower-capability platforms…to operate against adversaries that pose advanced threats to joint/multinational force efforts in any domain. To conduct follow-on sustained operations, or a sustained irregular warfare effort in a permissive or semi-permissive environment, AF forces primarily will use lower-cost/lower-capability assets.”

Today the F-16 comprises 50% of the USAF fighter/attack aircraft inventory (1,017 of 2,018 aircraft). At either extreme, the high-end of 187 F-22s is balanced almost equally with the 284 low-end centric A-10s. This forms an almost purely symmetric bell curve; most appealing to the eye. Ironically, this defines the polar opposite of the high-low mix that the US Air Force touts. Even worse, the force is still on a path of failed application marred by the context of how it defines itself.

Operations since 1991 have shown that the Cold War high-low mix that relies on large quantities of multi-role fighters is flawed. Today’s workhorse F-16 was initially envisioned as a complement to the F-15C. The F-16 has since evolved into a multi-role platform, predominantly supporting low-end operations during its 35 year history, especially the past 15 years. From 2006-2013, F-16s comprised 33% of all Close Air Support (CAS) sorties flown in Afghanistan and Iraq. This greatly exceeded the 19% of sorties flown by the CAS-specialized A-10 and indicates a force structure disparity. The naysayer would state that the vastly larger F-16 force leads to a proportionally larger percentage of sorties flown. After all, for a time F-16s were in both theaters simultaneously whereas the A-10 was not. Though this proves the entire point of the force disparity issue, a better comparison is the multi-role F-15E. With a force size more akin to the A-10, both aircraft models operated in Afghanistan from 2006-2013. The F-15E accounted for 12% of CAS sorties over the same period, which is actually more CAS sorties per inventory tail than the A-10 fleet.* Stating that this as a high-low force is a misnomer.

F-15E During a Combat Mission Over Afghanistan

(USAF Photo, SSgt Aaron Allmon)

The result is an under-utilized specialized force and an over-utilized multi-role force that has led to greater expense, both directly and indirectly. Beyond the higher operating costs, multi-role airframe lifetimes are approaching milestones limits due to flying extended duration low-end sorties for too many years. Furthermore, proficiency remains a concern for multi-role pilots. The Air Force readily admits it has been losing proficiency in contested (let alone highly-contested) environments for years, attributable to the low-end toll on the predominantly multi-role force.

Since the F-35 is due to replace the F-16, where does the F-35 fit into the high-low mix that the Air Force touts? It’s certainly not a low-end platform. The low end prioritizes quantity over quality, requiring massive quantities and absorbing higher levels of attrition to operate in medium and highly-contested environments. This is akin to the Cold War philosophy of the Soviet Union and Joseph Stalin’s argument that “quantity has a quality all its own.” It was proven extremely effective as a deterrent through positioning, posture, and parade. But, this strategy isn’t appetizing due to the risk and attrition-adverse culture of the US and its politics.

Despite how it’s advertised, the F-35 is not a high-end platform either. The enticing high-end force structure prioritizes quality over quantity, ostensibly solving the issues from a low-only structure. However, the pursuit of a high-only force structure is equally doomed and is sure to destroy an Air Force from within for three inter-related reasons: time, capability, and efficiency.

USAF’s 100th F-35 on Lockheed Martin’s Assembly Line in Fort Worth, Texas in 2013

(USAF Photo, John Wilson)

Time: Even in a fictitious world where economic realities don’t exist, the very nature of solely pursuing unproven technology makes the high-only structure an operational agility failure from the start. Unforeseen technological hurdles are inevitable and subsequently lead to delays. This has been proven in virtually every modern aircraft acquisition program for the past 20 years. Today, the F-35 program is seven years behind schedule due to its complexity. Time is a commodity that can’t be bought back, especially when it comes to maintaining relevant capability in a rapidly-evolving world. When the F-35 reaches Full Operational Capacity in 2022, it will be 21 years since it won the Joint Strike Fighter competition and the same year USB flash drives were invented (with a whopping 8 MB capacity). The world has changed, and it will continue to change.

Capability: The ability to operate in a contested environment is directly related to the capability one force has over another. The highest-end fight will always be a moving target progressing constantly to the right. This demands constant and never-ending leading-edge acquisitions to remain relevant and viable. In a high-only structure, an inordinate amount of resources must be endlessly allocated in this ultimately futile pursuit. The colossal, unsustainable drain on said resources ultimately results in failure due to the relationship of time and the evolving high-end. If this high-only force somehow overcame the hurdle of time, its glossy brochure of capabilities would succumb to an inability to sustain effective operations because of efficiency.

Efficiency: The continual high-risk financial investment makes a high-only mix politically untenable. Even if a high-only force were instantly fielded, the cost-exchange makes it unfeasible to operate a single platform equally across both ends of the high-low spectrum. Designing a force structure capable of the most dangerous course of action but inefficient at the most likely course of action is not a recipe for success. Today, if the F-35 instantly replaced every fighter currently flying in Operation Inherent Resolve, it would increase the cost of the campaign $4.8 million per day, a 44% increase to the current $11 million daily war estimate.**

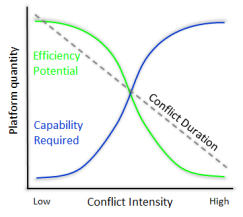

Looking at capability and efficiency, when applied across the entire spectrum of conflict a paradigm becomes apparent. This relationship is inversely proportional at both extremes: on the low-end great efficiencies with relatively low capability are required; on the high-end very high capability is required at the expense of efficiency.

Looking at capability and efficiency, when applied across the entire spectrum of conflict a paradigm becomes apparent. This relationship is inversely proportional at both extremes: on the low-end great efficiencies with relatively low capability are required; on the high-end very high capability is required at the expense of efficiency.

Finally, there is time. Throughout the history of warfare, there has been a discernible relationship between conflict duration and intensity. On the low-end, a long-term battle rhythm is endured and comparable to the pace of the entire war. At the other extreme, the high-end encompasses intense, short-duration conflict that is mostly representative of battles within the war. A war that starts at the extreme high-end of the spectrum will quickly slow as resources are expended and goals (or attrition appetite) are met, proportionally curbing intensity.

Regardless of how it deescalates, the realities of 21st century conflict must now account for intermingled state, ethnic, and religious actors coloring outside the lines drawn on a map or defined areas of operations. This type of graffiti war is characterized by protracted operations and increasing reliance on the other instruments of national power (diplomatic, information, and economic). Combined with a traditional force-on-force scenario, stalwart leadership enamored with 20th century warfare call this hybrid warfare. Today we should simply call it warfare. Today’s warfighter should be prepared for conflict to devolve into flat, long-duration operations with a wide range of multi-faceted objectives.

Because of all of these relationships, the high-end fight has the luxury of sacrificing efficiency for capability, whereas the low-end fight should always seek to optimize efficiency over comparative capability. Similarly, regarding the curves on the diagram, “capability required” is synonymous with “acquisition cost” and “efficiency potential” is synonymous with “operating cost”. All of this leads to a logical conclusion: an Air Force that wishes to remain relevant should always strive for a high-low mix structure. This provides the balance to efficiently achieve objectives across the full spectrum of operations and the best hope of attaining the operational agility that it seeks.

Ground zero of modernization must begin with assuring the future strategic asymmetry of the extreme ends of the spectrum of conflict, not in the middle as the F-35 proposes. Augmented by emerging technology, an Air Force can essentially expand the extremes of the high-end (capability) and low-end (efficiency) with purpose built, defined-contestment platforms. These new “lower-lows” and “higher-highs” are where the greatest gains in strategic asymmetry, and thus operational agility, can be achieved.

Where to start? On the low end, a new A-X based on the Embraer Super Tucano is no surprise. The Air Force looked into this idea less than a decade ago, and today we train Afghani pilots at Moody Air Force Base to fly their Super Tucanos. Maybe a bit more surprisingly, the A-X should be augmented by a low-end counter-air platform. This strikes against all conventional theory of air-to-air platform development in the past century. Well, conflict has changed considerably in the past century. Ninety-nine percent of all counter-air missions flown by the US in the past 30 years have been to maintain air superiority, not gain it. This includes no-fly zone enforcement and defensive counter-air. One could argue that the no-fly zone concept is overcome by the evolution and proliferation of counter-air systems, but the need to protect high value airborne assets will remain for the foreseeable future. Using the same principles of F-22-to-fourth generation fighter integration, a high-low package would be both complementary and asymmetric for multiple environments, with a plethora of scalable effects.

Today’s world evolution mandates a force revolution. Technology has created leaps of integration capability and synergistic effects that bridge the gap between the low-end and high-end. Overly investing in this trade-space with the F-35 is an archaic strategy, contradictory to published Air Force strategy, and certainly not a path to assuring air superiority and interdiction in the coming decades. The F-35 of today will be left behind.

Major Mike “Pako” Benitez is an instructor Weapons System Officer in the F-15E Strike Eagle with over 1,000 combat hours spanning multiple deployments. A prior-enlisted Marine and graduate of the US Air Force Weapons School, he has been involved in operational-level crisis action planning in both CENTCOM and EUCOM and has recently completed a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) fellowship. He blogs at The Bar Napkin.

* F-15Es weren’t stationed inside Afghanistan until 2008 and time-shared operations from Al Udeid into both Iraq and Afghanistan, slightly skewing the discussion towards the A-10. F-15Es left Afghanistan in 2012 and limited sorties were flown in 2013. The A-10 inventory fluctuated during these years, but averaged 330 aircraft. There are 210 F-15Es in the inventory.

** This assumes open-source F-35 $32,000 Cost per Flying Hour (CPFH), staged from current fighter bases and assuming an average operations rhythm of 40 flights flying 6 hour sorties over a 24 hour period. Fourth generation fighter average cost is $12,000 CPFH (A-10, F-16, F-15E, F-18C/D/E/F), sourced from Air Combat Command’s figures used in Flying Hour Program execution. Figure does not include weapon expenditure costs. Operation Inherent Resolve daily cost is $11 million, as updated on the official Department of Defense website: http://www.defense.gov/News/Special-Reports/0814_Inherent-Resolve.

Reblogged this on Defense Issues and commented:

US Air Force actually does everything to retire the A-10. One part of this is deliberate underutilization, forcing the F-15 and F-16 to do the work that the A-10 is far more suited for. As a result, USAF’s fast jet inventory has gotten worn out. As a result, A-10 pilots are not doing the job they are trained for, and fast jets pilots are doing the jobs they are insufficiently trained for. USAF is also eating itself alive, replacing the F-15 / YF-16 high-low mix with first the F-15 / F-16C high-medium mix and then the F-22 / F-35 ultra-high / high mix. Result of this is that USAF has to rely on very old machines, pilots that do not get anywhere close enough flying hours as they should, and a suboptimal force mix for either current or potential conflicts. Even in high-intensity conflicts, very high risk missions that may actually require stealth aircraft would be a minority; much would be taken up by the close air support, which again would require the A-10. And for COIN, even the A-10 is often an overkill – Embrear Tucano would be enough.

LikeLike